Filming: Color

Length: 155

minutes

Genre: Action/Adventure/Drama/Swashbuckler

Maturity: PG-13

(for battle sequences, thematic elements, and some sexuality)

Cast: Kevin Costner (Robin Hood), Morgan Freeman

(Azeem), Mary

Elizabeth Mastrantonio (Marion Dubois), Christian Slater

(Will Scarlett), Nick Brimble (Little John), Michael McShane (Friar Tuck), Alan Rickman (Sheriff of Nottingham), Brian Blessed (Lord Locksley)

(Will Scarlett), Nick Brimble (Little John), Michael McShane (Friar Tuck), Alan Rickman (Sheriff of Nottingham), Brian Blessed (Lord Locksley)

Director: Kevin

Reynolds

Personal Rating: 2

Stars

***

As a Robin Hood fan and an old-fashioned girl, I always

raised an eyebrow when I spied this modern film version perched on a library

shelf. I had considerable apprehensions on what they would do to remake my

beloved Rob, and really didn’t feel I had a strong enough stomach to handle it.

But eventually I figured I wouldn’t be able to make a proper comparative

analysis without at least giving it a once over, so I steeled myself and

prepared to deal with the foreseen mediocrity of modernization, changer in hand

for necessary fast-forwarding if the pain became too intense to withstand.

The film opens

during the Crusades where the wealthy young Robin of Locksley is languishing in

a Saracen prison. After offering to take the place of another prisoner who is

about to have his hand chopped off, he uses his

super-galactic-super-unrealistic fighting skills to launch a massive prisoner

revolt. In addition to freeing as many Christian prisoners as possible, he also

rescues a Moorish political prisoner named Azeem who agrees to return the favor

by saving his life someday.

Returning to

England with Azeem, Robin discovers to his horror that his father has been

framed by the evil Sheriff of Nottingham and murdered by a corrupt inquisition

that claims he practiced dark magic. In truth, it is the Sheriff who has been

dabbling in the occult with a run-of-the-mill-creepy-hag who claims to be able

to make him a success by reading the future in egg yolks. Robin, meantime,

tries to secure the aid of the rather prickly Maid Marian who he has not seen

since she was a child. Eventually, being hunted down as heir to the Locksley

estate, he is forced to take shelter in Sherwood Forest.

There he meets a

band of outlaws who are none-too-keen to take the riches-to-rags outcast into

their inner circle. But through his courage, innovation, and fighting skills,

he eventually assumes command of the disorganized bunch and turns them into a

hit-and-run fighting force capable of protecting the common people from the

tyranny of Prince John in hopes that King Richard will return and validate

their stand. After an epic battle for possession of the outlaw camp, the

outlaws hold their ground, but Robin is believed to be dead. Meanwhile, the

sheriff men capture a handful of peasant children and use them as hostages to

force the well-to-do Marian to wed him.

More trouble

unfolds when Will Scarlett, a young outlaw who chafes under Robin’s command,

offers to be a spy for the sheriff to find out if “the Hood” is still alive.

But in the process of doing so, an even more unexpected twist is in store as

the two men discover they are really long-lost half-brothers due to their

father’s liaison with a commoner that Robin broke up! (Dysfunctional family

plot…joy…) Anyway, their common bond is the link that reunites Robin’s band,

and the battle to free the hostages, rescue Maid Marian, and overthrow the

tyranny of the Sheriff is underway.

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves is another

big-budget would-be epic that puts glamour before substance and tries to pair

historical fiction with fantasy/sci-fi in a way that is nothing short of

ridiculous. Artistically, it has some entertainment value here and there, but if

you are like me, and prefer to actually “get the feel” of a past time period as

opposed to having it exchanged for miss-match portrayal, this really isn’t for

you. Modernizations are rife from beginning to end, trying to make it all more

trendy, multi-cultural, and feminist. Superman action sequences are

off-putting, as are the crude, rude, and lewd actions and linguistics that are

liberally sprinkled throughout.

Whoever decided to

bestow the honorable title of “Prince of Thieves” on Kevin Costner should have

been run out of Hollywood on a rail. I mean the guy reeks of 1990’s California,

has trouble mustering up even the vaguest hint of an English accent, and simply

cannot mesh with even an obviously shoddy depiction of 12th century

England. Mary Elizabeth

Mastrantonio’s depiction of Maid Marion is something of a generic girl-power

model that conveys too little of the discreet sparkle and charm that I have

always found delightful about her character. Plus, she seems to take pleasure

viewing a naked Rob swimming in a lake! Her plump lady in waiting also proves

to be a lame comic relief figure.

The Sheriff of

Nottingham is disgustingly overdone, with his topless harlots and hoaky witch

sidekick who claims to be able to discern the future in breakfast food. The

most disturbing sequence has to be his attempt to rape Marian, which was

totally over the top and unnecessarily graphic. Little John is shown as being a

foul-mouthed ruffian who’s pushed around by his formidable wife, Fanny. Friar

Tuck is a drunken wreck who sings filthy ditties, only to be slightly

rehabilitated when he is appointed chaplain at Sherwood. Still he stands out as

a bloated bigot when dealing with the Muslim Azeem. Again, he does redeem himself

to some extent by inviting the Moor to share a drink with him after Azeem saves

Little John’s wife. But overall, he is fairly unlovable and a generally a

disgrace to the priesthood.

That having been

said, there are some interesting twists in the plot. Getting to see Robin Hood

in the Holy Land was a rare treat, and having him offer to have his hand cut

off in the place of Marian’s was a gesture in keeping with his character.

Having said brother charge Robin with caring for Marian after being mortally

wounded is interesting as well. I thought Azeem was okay as an additional

sidekick, and I had no problem with having the Islamic perspective introduced

to the plot. One of the best lines from was when a little girl asks him why his

skin is so much darker than her own. “Because Allah loves diversity,” he

responds.

Of course, the

Crusades are generally cast in a bad light. Lord Locksley, portrayed as a man

of principle, is against his son going to fight in Palestine, saying that it is

vanity to force one’s religion on others (which completely misses many of the

reasons why the Crusades were actually fought, but anyway…). Frankly, Islam has

been extremely intolerant towards other religions during the course of its

history, and making Eastern culture seem more spiritually and intellectually

enlightened than the West is hogwash. It is true that technological advances

were definitely made in Europe as a result of contact with the East, as it is

true that later the East would make similar advances through contact with the

West, as is portrayed (negatively, may I add) in The Last Samurai.

Some of Azeem’s lines and actions

are admittedly humorous, like his declaration that he would never let a man

sneak up on him “who smells of garlic, while a wind is blowing to the back of

me.” He also seems to takes his sweet time to repay Robin Hood for saving his

life, always putting his rather drawn-out prayer ritual first, but in the end

proving that he really knew what he was doing the whole time. There is some

genuinely good banter between them, especially when R.H. is stunned by the

projection of Azeem’s telescope. “I don’t know how you English are winning the

war,” the Moor sighs, referring to The Crusades. “God only knows,” Rob returns

brightly.

The portrayal of

the Church overall may not be glowing, but it could have been a lot worse. The

bishop is corrupt, Friar Tuck is a lout, and the Crusades and the Inquisition

are portrayed darkly. However, it is also shown that Robin and Marion are both

practicing Catholics, and that the bad guys plunder churches and misuse humble

country clergymen. R.H. returns the stolen articles to the Church. One major

motif that stands out in the film is the cross pendant hung on Lord Locksley’s

grave which Robin assumes as a symbol to mete out justice to his father’s

murderers.

With regards to

battle sequences, the long-staff duel in the river was exciting enough, if

rather drawn out, with Little John using less than gentlemanly language. Later

on, it was interesting to see Sherwood Forest laid out as an actual defensible

compound with tree-houses, bridges, and an ingenious rope-swinging system

(which Rob and Marian make romantic use of!). The battle is not your average

woodland skirmish, but a full-scale assault and counter-attack. It’s cool, if a

bit over-extended. The hokiest part is when Costner-Hood is thought to be dead,

but then reappears, unexplained, out of the forest mist! The last battle is way

overblown, and the hanging sequence last a forever before the suspended

personages are finally rescued. But really I think the duded would naturally

have been deceased by then!

To its credit,

this version, as innovative as it aspires to be, it does not abandon the bare

essentials of the Robin Hood narrative we all know and love. R.H. is a

full-fledged hero, not a Russell Crowe anti-hero, and his dedication to the

English people is pure. One scene I find particularly stirring is when he when

he returns to England from Palestine, and kisses the ground. Another scene I

appreciated was when Robin explains to Marian how he went from being a play-boy

to the man of the people: How on the Crusades, he had seen high-born men turn

and flee, while a low-born man had pulled a spear from his own body to defend a

wounded horse. Hence, he discovered that nobility is made manifest through acts

more than birthright.

So my overall

synopsis of Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves

is that it is a newbie hip-flick, trying to remake beloved classic and somehow

give it more spring in its step. As I’ve outlined, it does have its positive

points, but perhaps the main problem with the whole production is belief that

it is even necessary to modernize all things old in order to keep up with the

times, instead of letting modern audiences learn to appreciate an older setting

and comportment that does not necessarily perfectly coincide with their own.

This is all the

more distressing since our present tee-shirt and flip-flop era has almost

completely lost its sense of modesty and decorum, both in daily life and on the

Silver Screen. The lessons and charm of the past seem to be lost to the masses,

which is nothing less than tragic. If you want to watch superior Robin Hood

adaptations, check out the film versions with Errol Flynn and Richard Todd, the

TV series with Richard Greene, and the Walt Disney animal cartoon. They beat

California Costner-Hood of Smoggy Sherwood by a running mile.

|

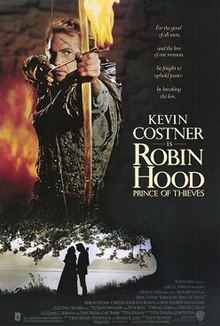

| Robin Hood (Kevin Costner) meditates at his father's grave |