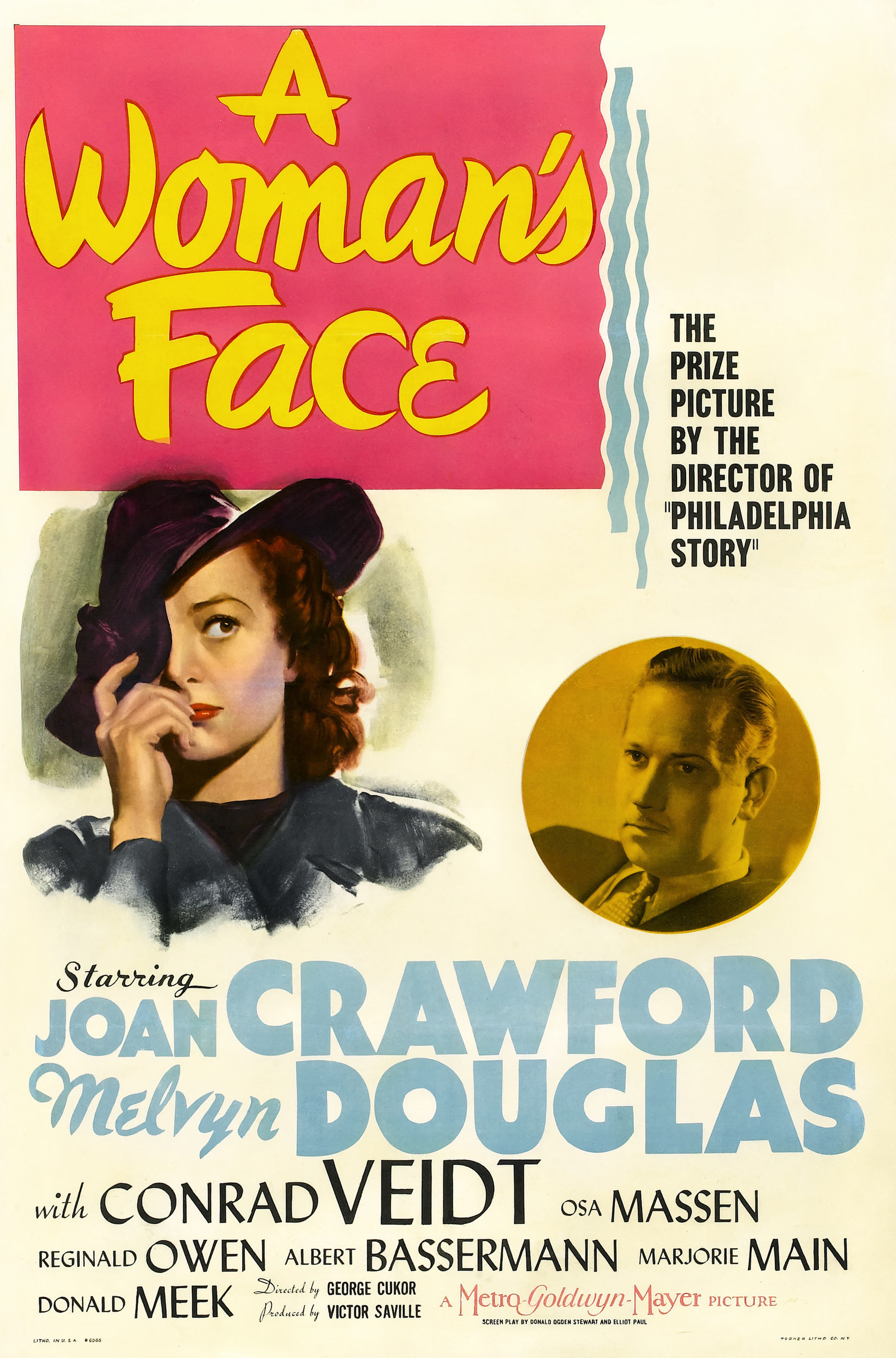

Year: 1941

Filming: Color

Length: 105 minutes

Genre: Drama/Noir/Suspense

Maturity: PG (for intense thematic elements)

Cast: Joan Crawford (Anna Holm), Melvyn Douglas

(Dr. Gustaf Segert), Conrad Veidt (Torsten Barring), Osa Massen (Vera Segert), Richard

Nicholas (Lars-Erik Barring), Connie Gilchrist (Christina Dalvik), Reginald Owen (Bernard Dalvik), Albert Bassermann (Consul

Magnus Barring), Marjorie Main (Emma Kristiansdotter),

Director: George Cukor

Personal Rating: 4 Stars

***

Certain movies come

to you by complete surprise, and are surprisingly well worth the viewing. In

the case of this film noir diamond-in-the-rough, it just so happened to be

among at the end of a VHS that was included in a bargain-bin at a yardsale.

When I first started watching it, just to see what it was, I was none too

impressed. The scenes were dreary, and the story-line seemed quite hard to

follow. But as I stuck with it, I became immersed in this edge-of-your-seat

thriller that feels near Hitchcockian in mood.

Set in 1940’s

Sweden, Joan Crawford stars as Anna Holm, a woman with a scarred face and a

scarred heart, running away from her torrid past at the same time as she lashes

back at the world for all her past sufferings. Operating a black-mail ring and using

a restaurant chain as a front, she is given a packet of clandestine love

letters stolen from the vain and frivolous Vera Segert, who frequents one of

the restaurants. Torsten Barring, the mysterious stranger who stole the

letters, wants to become partners with Anna, who he admires for her cunning

criminal mind in spite of her disfigured face.

Anna is

unaccustomed to the attentions paid to her by Barring, and soon falls head over

heels in love. Her low-life cohorts mock her out and threaten mutiny, but she

assures them that the letters from Vera will enable them to blackmail her and

make a profitable sum. But when she goes to the home of Mrs. Segert to extort

money from her in exchange for the letters, she accidently runs into her

husband, Dr. Gustaf Segert, a respected surgeon who sees Anna’s face and

believes he can restore it. Realizing this might be her only chance for

regaining her former beauty, she agrees to undergo the experimental procedure,

even though it is known to be dangerous.

Over the course

of multiple agonizing procedures, Segert is intrigued by Anna’s elusive

personality, and comes to admire her determination and strength in comparison

with his shallow, unfaithful wife. However, he still senses that there is something

about Anna that is dangerous, and even after the operation is a success and her

face is restored, he questions whether the beauty of her soul can be restored

so easily. Still, after she leaves, he has hope that no matter what her past

might have been, she will use her new-found beauty to make a fresh start for

herself in the world.

But still desperate

to secure the love of Torsten Barring, Anna becomes enmeshed in a plot to murder

his young nephew, Lars-Erik, so he will inherit his uncle’s vast estate in the

mountains. Although initially hesitant, she eventually agrees and applies for a

job as governess for Lars-Erik. But as she gets to know Torsten’s affable uncle,

Consul Magnus Barring, and the adorable little Lars-Erik, she begins to feel

like a human being again, and her own icy heart begins to thaw. Will she have

the courage to break with her dark past and forge a brighter future, or will

she be defined by the scars that once disfigured her face?

A Woman’s Face is one of those obscure,

unusual little movies that turns out having profound examinations of the human

condition. It stands out in the film noir genre as having a “method to its

madness”, so to speak, and cutting to heart of the true meaning of beauty and love.

Although the first scene opens in a courtroom where Anna is being tried for

murder, the rest of the story is told through flash-backs based on the testimony

of the witnesses. I initially found this technique rather confusing, but after

a while, I began to appreciate it, and even found it particularly gripping.

As fits the mood,

it was shot in black-and-white and emphasizes the play between light and shadow,

just like Anna’s own struggle between. We only catch several direct glimpses of

Anna’s scarred face, because she wears her hat low, and this adds to the

mystery as to whether or not she has been made “beautiful” when she is in the

court room. The first time we see it is when Barring approaches her with the

clandestine letters, and hides his shock by pretending he merely saw that she

had something in her eye. It is this gesture that makes Anna feel accepted by a

man at along last, and enables Torsten to manipulate her for his own ends.

The cast is superb,

and does an excellent job acting out the diverse roles. I have never been a

major fan of Joan Crawford, and yet she really does shine in this film and show

her talent for portraying a woman crossed between malicious intent and an

almost pathetic desire to return to innocence. Melvyn Douglas is a very steady,

very logical Dr. Gustav Segert, who comes to realize that for all his medical

expertise and ability to heal the scars on Anna’s face, he is woefully unable restore

the beauty of her soul. Still, he is there when she needs him, and stands up in

her defense at the trial. Conrad Veidt makes a deliciously elegant, chillingly

slithery Torsten Barring, who reveals the full extent of his evil nature a

little at a time.

As much as I feel

for Dr. Segert’s marital woes, as I Catholic, I don’t believe that necessarily

validates him having an extramarital romance. Now, I’ll grant that his wife is

cheating on him, and is totally self-consumed, so he might have grounds for

annulment there. But still, I don’t know if just jumping from woman to woman is

the right way to handle the situation! That having been said, he sees something

beautiful in Anna that enables her to break the dark bonds that have ensnared

her, and she is finally able to accept and receive true love. It’s interesting

to note that Anna made a study of famous love letters throughout history, from

the likes of John Keats, even in the darkest periods of her life.

I love the Swedish

setting! It’s so unusual, and dark, and almost mythic. I enjoyed seeing how the

Swedish court proceedings unfolded, and the unique customs such as taking an

oath before testifying “as a son/daughter of a Christian”. But one thing

strikes me as being rather strange: how is that this film is made (and

seemingly set) in 1941 Scandinavia, and yet there is no mention of the Second

World War? I mean, I know Sweden was neutral, but I’m sure it had to be

permeating the news! But then again, perhaps the heart of the movie really was

about the war after all, and Torsten Barring was just another form of Adolf

Hitler. His declaration that some people are entitled to be evil and to conquer

is the thing that finally shakes Anna out of her infatuation with him. At any

rate, drawing the parallel is certainly a valid one.

Lars-Erik is

actually the key character in the movie, whose innocence strikes a chord deep

within Anna that pulls her out of the darkness and into the light. Although she

has been accustomed to being treated as sub-human because of her scarred face,

and thought she had to be a she-wolf in order to survive, his unconditional

love for and trust in her awakens her stifled conscious and the realization

that she can be good. It is symbolic

that at a party she is dressed as a local Swedish saint who is patroness of

children. Barring mocks her for this, and she assures him she is not completely

on the side of the saints. And yet the chance for it has been opened, and she

can bear to turn her back on it completely.

The turning point

in the movie takes place on the ski lift in which Anna is riding with

Lars-Erik. According to Barring’s plan, she is supposed to unlock the gate and

let the lad fall to his death. Although she starts to do so (and the close-up

shots seem like something straight out of an Alfred Hitchcock production), she

realizes that she cannot, and pulls

him back to safety. When Torsten realizes she will not follow through with his

plan, he kidnaps young Lars-Erik and takes off with him on a sleigh. Anna

realizes his devious intent and alerts Dr. Segert, who also happens to be

visiting Consul Magnus. Then the two of them set off on a break-neck chase to

rescue the child…and the unexpected series of events that lead Anna to be

accused for murder before the court unfold.

A Woman’s Face is a suitably dark yet

beautifully deep film noir drama about the powerful reality that ever person

has the chance to be redeemed and start anew, no matter their checkered past. It

also shows that beauty is something that comes from within, and defines the

essence of the person, as opposed to mere physical traits. Couple this

meaningful moral with artfully rendered suspense, exquisite performances, and a

break-neck sleigh race in the Swedish mountains, and you’ve got a film not to

be missed!