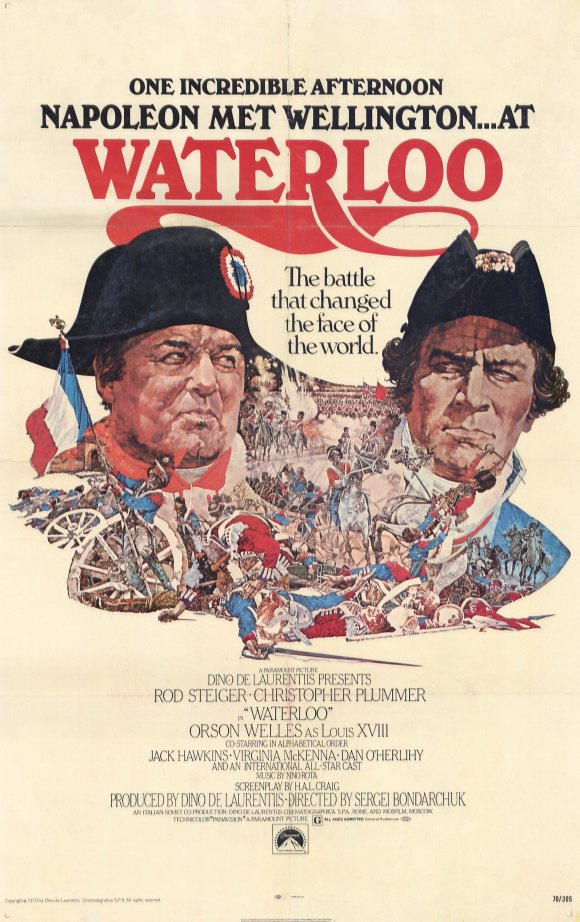

Genre: Drama/History/War

Rating: PG (for mild language and battle sequences)

Personal Rating: 4 Stars

***

Christopher Plummer stars as the dour yet

dogged Duke of Wellington who must pit his outnumbered troops

against the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte, who recently escaped from

captivity on the Isle of Elba. The two armies converge on a rain-drenched

Belgian field near Waterloo, and Wellington determines

to hold his position until Prussian troops arrive to defeat the

French Emperor once and for all.

Napoleon, meanwhile, broods about his

future and causes more trouble for himself by issuing impulsive commands

to his officers. Several sub-plots in the film include one about dashing young

British officer who is haunted by premonitions of his own death and

another about a cheeky Enniskillen Dragoon who is always getting

into mischief.

Waterloo is one of those quinisentially

British movies with a sense of dark humor underpinning the dialogue. Wellington

is cracking witicisms right and left as shells burst around him, revealing the

stiff-upper-lip cool under fire of his class and country. Indeed, this is

sometimes taken to a humorous extreme, and while Wellington was certainly known

to have an acerbi wit, I highly doubt the banter continued quite as light-heartedly

throughout one of the most intense battles of world history!

The British have

always enjoyed gallows humor, and portraying themselves as possessing it, but

this unrealistic flippancy risked turning Wellington into a comic relief figure

in contrast with the brooding and intense Napolean. Ultimately it didn’t do

justice to the complexity of his own multi-faceted personality, and he become

something of a characature for his nation.

In spite of this,

Christopher Plummer makes up for the early fooling around by demonstrating his

amazing acting ability in later stages of the battle. This is most apparent

when trying to demonstrate Wellington’s increased distain for war. It starts

when the young officer he has been trying to protect stands up in the middle of

a British square to encourage his men, shouting “Think of England! Think of

England!” He is shot in the head by a French soldier, and falls dead.

Wellington stares blankly at the spot where he fell, and the unreadable

expression on his face speaks volumes.

Later, a second

young aid is shot in the back immediately after Wellington gives him an order.

He staggers forward several paces in agony, trying gallatnly to stay on his

feet, before finally collapsing in the arms of some nearby soldiers. This time,

Wellington cannot even look, and awkwardly turns his eyes down, blinking

nervously and swallowing hard. Its becoming increasingly apparent by his body

language that his struggle to avoid displaying emotion is becoming harder.

Then in the last

moments of the battle, when Wellington finally has cause to celebrate after

turning the tide, his friend Lord Uxbridge reels in his saddle and cries out,

“My God, sir…I have lost my leg!” Wellington does not even look at the leg, but

rather stares at the man’s face with a look of shock and horror, still

struggling to supress his own emotions. “My God, sir,” he murmurs, in a daze.

“So you have.” Then he supports Uxbridge as he falls against him, and cries out

for a medic.

Finally, Wellington

struggles to deal with the fact that his Prussian allies are far more set on

vengence against the French then his own troops, and set about butchering them

without mercy. Wellington tries to play the gentleman, and procure the

surrender from a group of French survivors who are determined to resist. As he

waits for the answer from the survivors, it is obvious how tense he is, hoping

beyond hope they will take the mercy offered. They don’t, and he is forced to

use the artillery on them. Once again, he closes his eyes, and looks down.

At the very end

of the film, we get to see Wellington one more time, riding about the field,

littered with wounded and dying men and horses, as scavengers pull the clothes

off the bodies. Again, his face is almost a complete blank, scanning the

horrific scene. Then suddenly, his eyes fall on a young Scotsman, lying dead in

his kilt, with his pipes lying near him. The wail of the pipes is heard, as if

in a flash of Wellington’s memory, the music builds, and he has a visible surge

of emotion, which he manages to pull himself out of with the greatest struggle,

before riding off the field. Through all this, you get the feeling that the

initially haughty and unapproachable Wellington, and witty and dapper nobleman

who never gets flustered, is far more human and relatable than all that. First

appearances can indeed be deceiving.

The battle footage

is spectacular, but the movie also spends time on the uneventful periods

between the fighting. Since this is a European production, the pacing is

slightly different from what most Americans are accustomed to. It's more

introspective and internal, giving one insight into the thoughts of the characters

as well as their actions.

Some people find the lulls in

the plot to be boring, but I think they let the viewers get a good

taste of all dimensions of the conflict, both physical and emotional.

Also, it gives the viewer the chance to catch a glimpse of the hum-drum

duties of early 19th century soldiering.

The traditional

British folk-songs such as “Macpherson’s Farewell”, “Boney Was a Warrior,” and

“The Girl I Left Behind Me” that are weaved into the scenes are also a nice

flavoring. I definitely think this film a nice overview of the last phase

of the Napoleonic Wars that culminated in 1815. History lovers will be

thrilled.

|

| The Duke of Wellington (Christopher Plummer) at the ball in Brussels |